The House Builders Came

The development of housing in Rayners Lane was linked to the growth of the railways in the area.

The last Daniel Hill died in 1906 and his heirs sold the land (including the Rayners Fields) to Metropolitan Railways in the 1920s. Then the house builders arrived.

Although the Rayners’ cottage was the only building in the area at the time, The Metropolitan Railway was already buying up land in the area for future development. Unlike other railway companies, which were required to dispose of surplus land, The Metropolitan Railway was in a privileged position with clauses allowing it to retain land that it believed was necessary for future use. The company believed housing development could provide a long-term source of income, luring the wealthy out to the ‘countryside’ with cheaper season tickets. In 1887, the Metropolitan Surplus Lands Committee was formed to manage the company property that was intended for development and Metropolitan Railway Country Estates (MRCE) was created.

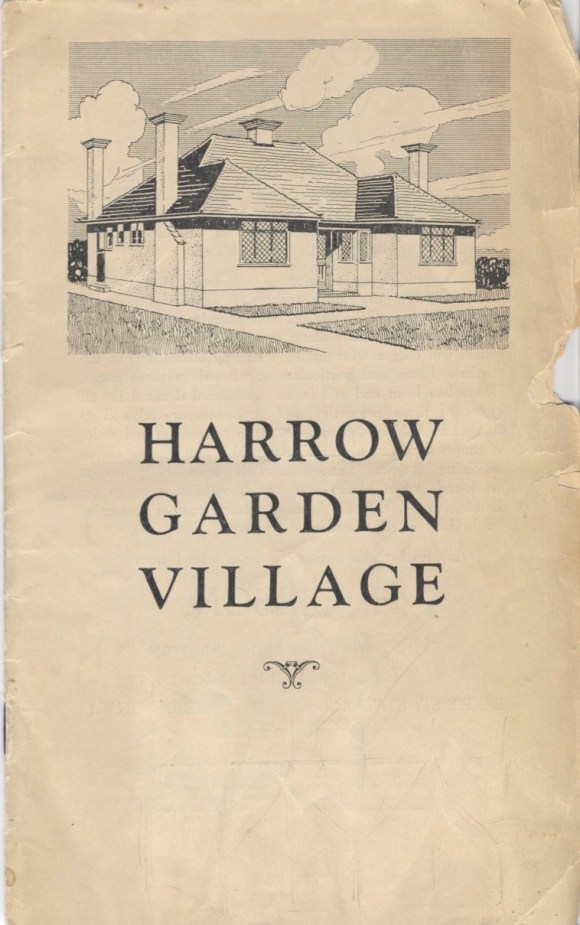

The first major development in Rayners Lane became known as Harrow Garden Village, a residential project designed by E.S. Reid and planned according to garden suburb principles.

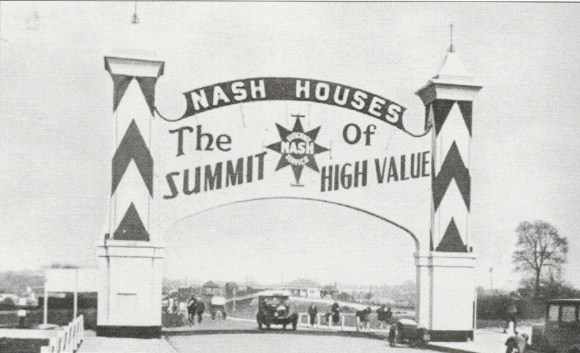

Further expansion took place around 1930, when Tithe Farm, located south of the Piccadilly Line, was sold to T.F. Nash Ltd. This became the largest development in the Pinner area, featuring predominantly affordable terraced housing.

Other notable builders of the are include Cutler and Pickering.

How The Landscape Changed

In 1930 the landscape is still very rural. At the top of this picture in the middle you can see The Close and the row of trees of the original Rayners Lane. To the left of this, where the trees start to thin out you can just make out the remains of the Rayner Cottage.

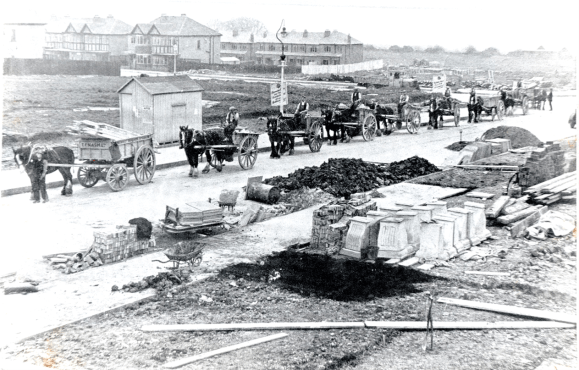

The Building Process

Selling Rayners Lane

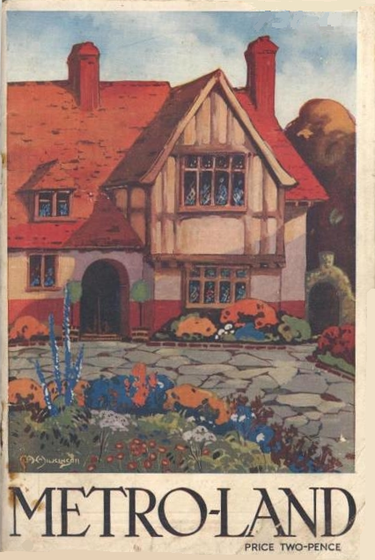

The marketing strategies of the two developers were as divergent as their housing models. While MRCE relied on the prestige of the “Garden Village” concept, with Harrow Garden Village as their flagship developement. As these developments were driven by The Metropolitan Railways, not just in Rayners Lane but in surrounding areas, the term “Metroland” was coined to promote them. The company marketed Metroland as a kind of semi-rural paradise: clean air, modern homes, green spaces — all within commuting distance of central London. This was aimed at middle-class families seeking to escape the crowded, polluted inner city while still maintaining easy access to work. These brochures used idyllic imagery and persuasive language to sell a dream of modern suburban living – the picture of the cottage in Rayners Lane was used to promote this despite the fact it was bulldozed to make way for new houses!

T.F. Nash Ltd. was a master of promotion. To attract buyers to its more distant plots, the company erected a temporary 35-foot illuminated arch over Alexandra Avenue in 1933. They also provided courtesy cars for prospective buyers, a “clever trick that disguised quite how far these houses were from the station”. This distinction in target market and housing style (semi-detached vs. terraced) demonstrates that even within the idealised “commuter paradise”, a deliberate social and economic stratification was being engineered.